Murder, Memory, and Martyrdom: The Assassination of Governor William Goebel

AWARDED SPECIAL PROJECT AWARD OF THE KENTUCKY HISTORICAL SOCIETY, 2020

Who was William Goebel? Why was he assassinated? By whom? Why does it matter?

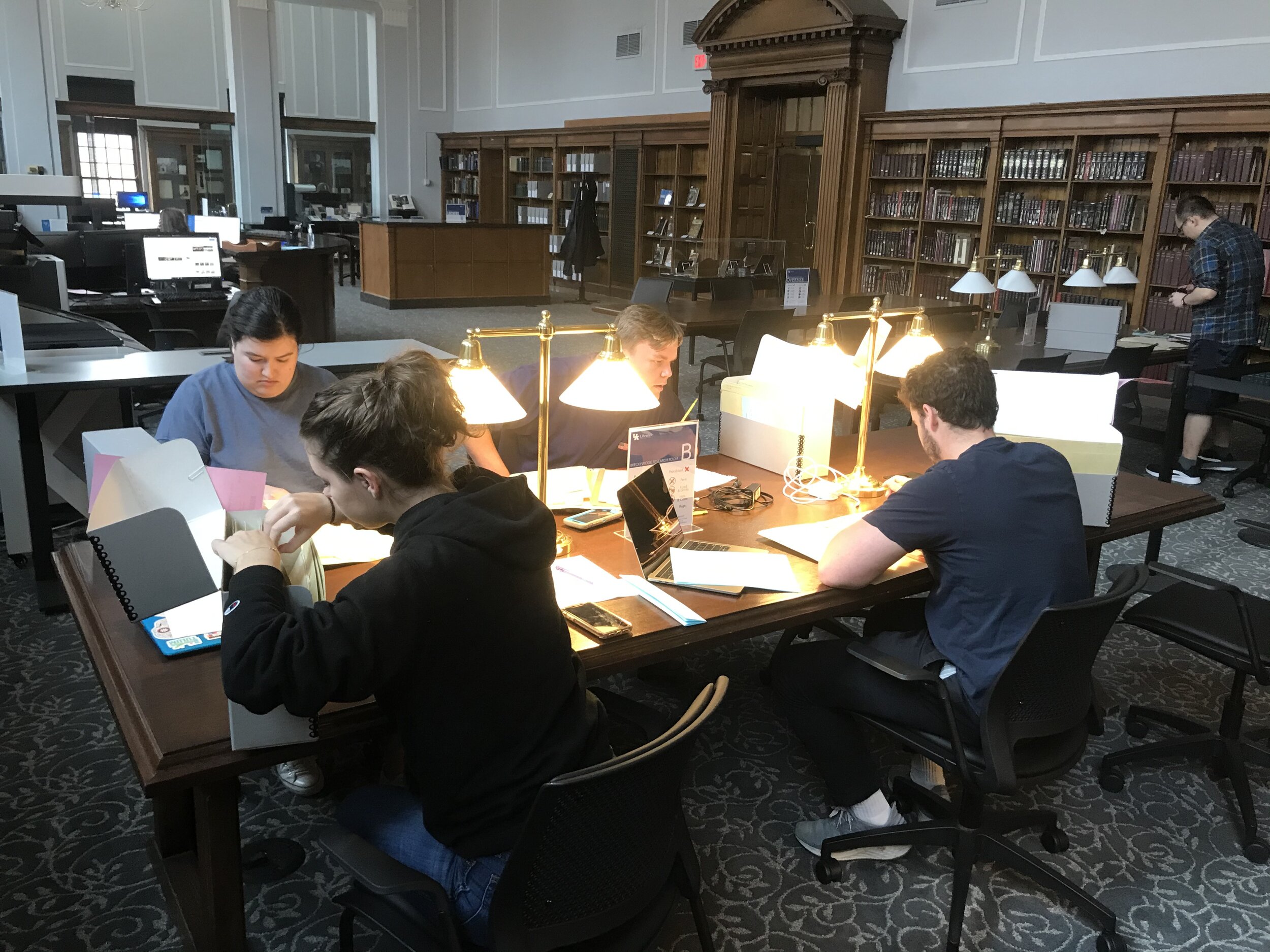

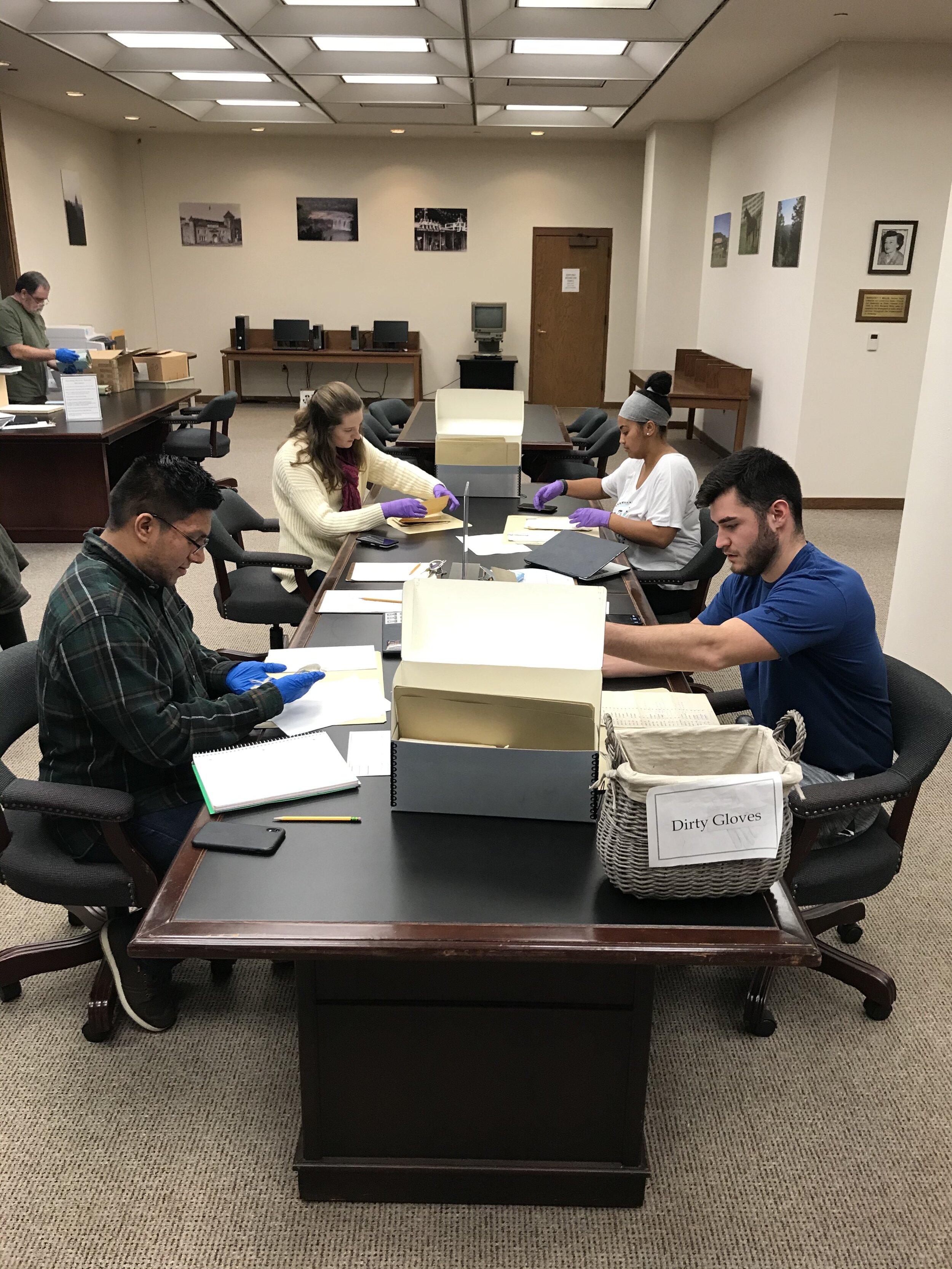

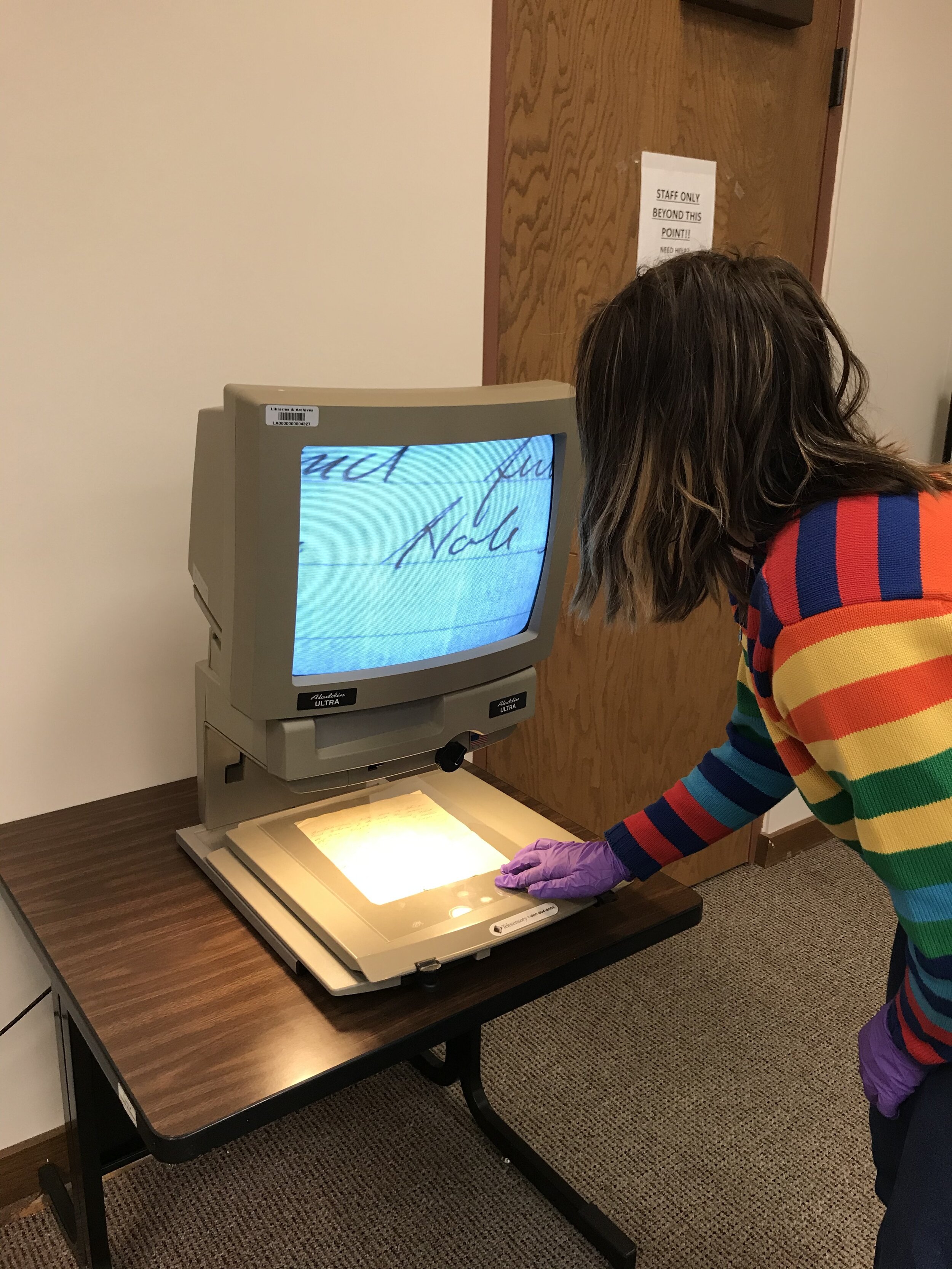

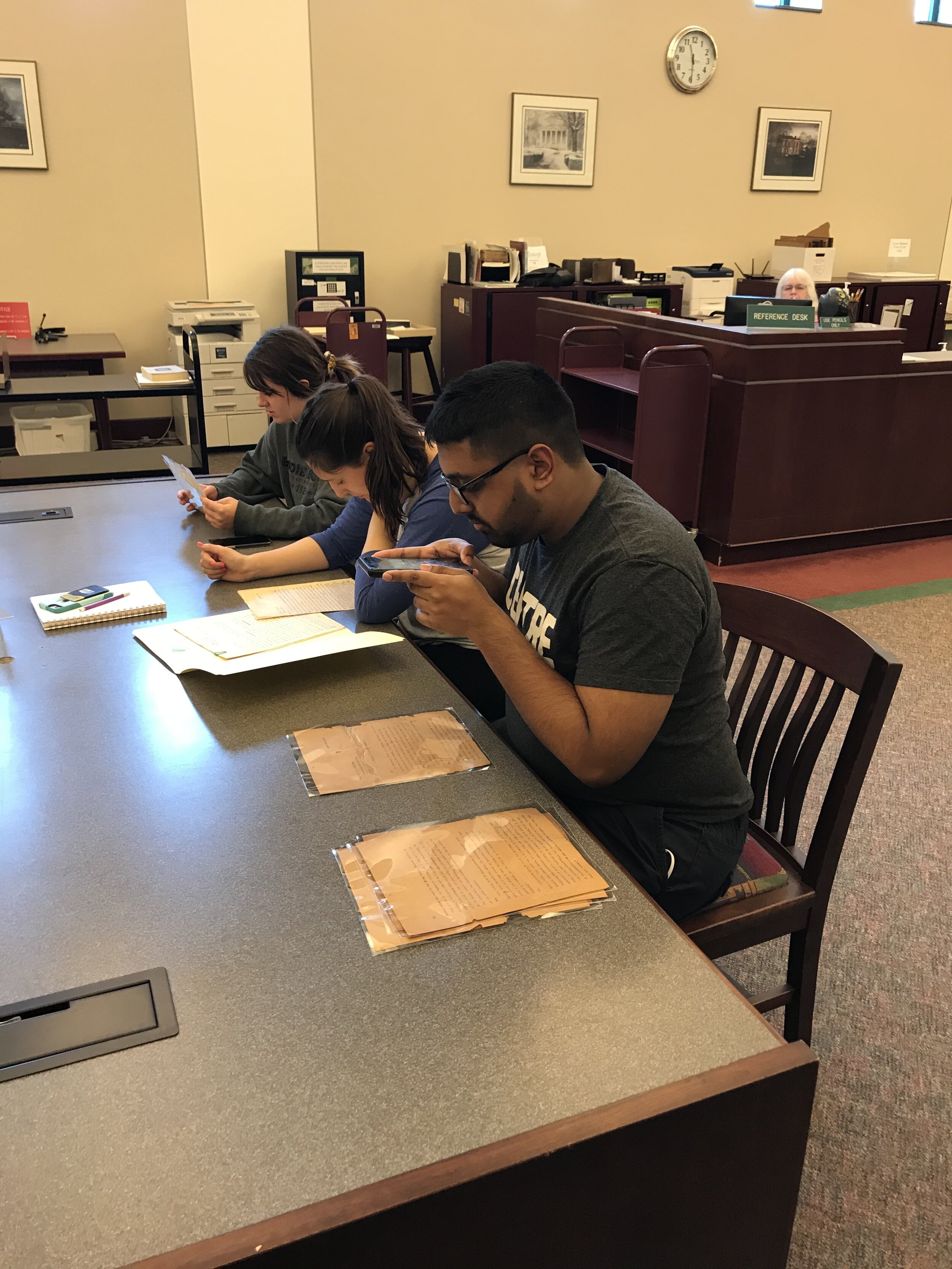

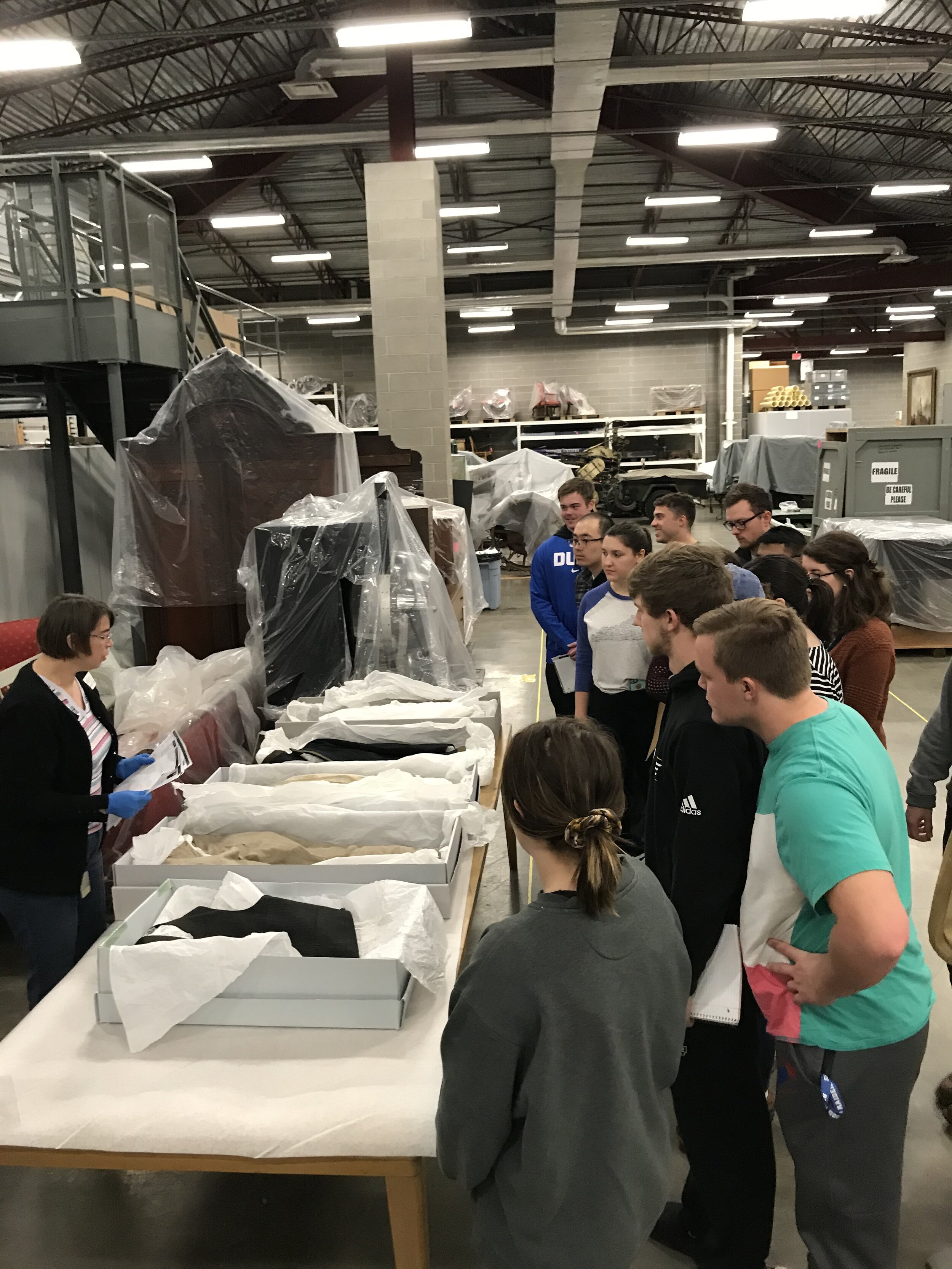

Governor William Goebel—the 34th Governor of Kentucky (1900)—is the only American governor to die from an assassin’s bullet while in office. In January 2020, 30 undergraduate students at Centre College spent over 270 hours working in archives throughout central Kentucky to reassess the history and contested legacies of Governor William Goebel’s assassination. They completed their research during an upper-level history course entitled Assassins (with Dr Jonathon L. Earle). They interrogated court records, detective reports, eye-witness testimony, receipts, music, newspapers, telegrams, and correspondence between the alleged conspirators, including Centre College alumnus Caleb Powers, Secretary of State of Kentucky (1900), who supposedly orchestrated the murder.

The outcome of the students’ research is the following six-part podcast series. By exploring the history of assassination in early twentieth-century Kentucky, this stream raises broader insights into cultures of violence in the Ohio River Valley following the American Civil War, changing economies during Reconstruction, judiciary corruption, and the politics of memory and memorialization. By the mid-1960s, several high-profile assassinations throughout the United States, including the murder of President John F. Kennedy, overshadowed the public memory of Goebel.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

To model their production, students looked toward Throughline, NPR’s premier history podcast. PRX offers a useful series of introductory videos on producing podcasts. We wish to thank the fantastic staff of the Kentucky Historical Society, in particular Cheri Daniels, Carol Bolton Easterly, Greg Hardison, Julie Kemper, Stuart Sanders, Deana Thomas, and Deborah J. Thompson. At the Kentucky Department of Libraries and Archives, we are grateful for the research support of the staff and Walter Bowman. At the Special Collections of the University of Kentucky, we are indebted to Jay-Marie Bravent, Katie Henning, Matt Strandmark, and Daniel Weddington. The Filson Historical Society provided additional archival support, as did Beth Morgan and Mary Girard with the Special Collections of Centre College. For their time, expertise, and interviews, we would like to give a massive shout out to Carol Bolton Easterly and Drs Bob “T.R.C.” Hutton, Anne E. Marshall, Patrick Lewis, and Andrew Patrick. Episode Four also drew from the musical assistance of Kevin MacLeod with Incompetech. Technical support was expertly provided by Todd Sheene and Candace Wentz, with the Center for Teaching and Learning at Centre College. Last, we wish to thank Centre College, who generously funded this project.

Podcasts

Governor Goebel Gets Got. This episode touches upon Goebel’s path to the 1899 election, the events of 30 January 1900, and the primary sources that the political murder produced.

The ‘Duel’ Nature of Kentucky Politics. Here, we explore the broader history of political violence in Kentucky, from cultures of feuding to the Black Patch Wars in western Kentucky.

Through the Window. In this episode, we tell the story of the assassination through each of the alleged perpetrators behind the window where the assassin’s bullet was fired.

Mountain Men, Mobs, and Political Murder. This podcast explores the politics of political mobilization in eastern Kentucky and the legacies and ‘invention’ of cultural stereotypes in the Appalachian region.

Assassination on Trial. We use this episode to discuss the multiple trials of the accused conspirators, James Howard, Caleb Powers, and Henry Youtsey.

Making of a Martyr. This podcast asks, how did William Goebel go from a being prominent politician to a primarily overlooked governor in the region’s political history? And what does this say about shifting cultural and political landscapes in Kentucky politics?

States of Violence: Frontiers, Empires and Slavery

The assassination of William Goebel was the outcome of a much older and larger history of political violence in the region.

Schik, ‘Daniel boone’, c. 1890

The early establishment of Kentucky was fraught with episodic and structural violence between aspiring settlers and Native American communities. By the late eighteenth century, American and Kentucky settlers weaponized the fictions of a barbaric and savage ‘frontier’ to legitimize attacks against Chickasaw, Shawnee, Yuchi and Cherokee communities.

Source of Image: Library of Congress/LC-DIG-ppmsca-23155/‘Drawing shows Daniel Boone in a stock heroic pose preventing an Indian holding a hatchet from harming a woman and baby, while a dog bares his teeth’

Lewis & Conrad, ‘

A correct map of the seat of war’ 1812

The War of 1812 resulted in the Star-Spangled Banner and the burning of the White House. During the War of 1812, the State of Kentucky provided over 25,000 soldiers to fight Britons and Native Americans. According to the Register of the Kentucky Historical Society, 5 out of every 6 eligible men in Kentucky fought, which enabled the Commonwealth to mobilize over 36 regiments. By the end of the War, Kentuckians experienced more battle causalities than every other state—combined.

Source of Image: Library of Congress/G3711.S42 1812 .L4 TIL

George Henderson, Interview, Garrard County, 1941

As Anne E. Marshall shows, enslaved Americans comprised 6.2% of Kentucky’s population in 1790. The enslaved population constituted 24% of the state’s population by 1830. According to the 1850 census, 28% of white families owned slaves, whose labor produced Kentucky’s booming large-scale hemp and tobacco economies. In this interview, George Henderson, of Versailles, Woodford County, recalls the systemic violence that accompanied economic development in the Bluegrass.

Source of Image: Slave Narratives: A Folk History of Slavery in the United States from Interview with former slaves (Library of Congress, 1941)

One State: Two Nations

The overwhelming majority of Kentuckians did not support Confederate secession, and the majority of its combatants served in the Union Army. That the state birthed the two respective presidents of the Civil War, born within 100 miles of each other—Abraham Lincoln outside of Hodgenville, and Jefferson Davis in Fairview—illustrates the state’s bifurcated position during the War. Throughout the early 1860s, Lincoln struggled to control the politics of Kentucky. He reflected in one letter: ‘I think to lose Kentucky is nearly the same as to lose the whole game. Kentucky gone, we can not hold Missouri, nor, as I think, Maryland. These all against us, and the job on our hands is too large for us’ (Lincoln to Senator Orville Browning (R-Illinois), 22 September 1861).

IMAGES (BELOW): L) Abraham Lincoln, 3 June 1860; R) Jefferson Davis, c. 1860

Source of Images: Library of Congress/Prints and Photographs Division

Cultures of Assassination and Dueling

Following the Civil War, Kentucky developed one of the most robust dueling cultures in the United States, which was propelled by land disputes and much older conceptions of honor and political authority. During the second half of the nineteenth century, targeted killing became a key political mechanism to secure and contest power. The ubiquity of political murder was covered extensively in the national press, as noted in the following three articles from the New York Times: ‘Riotous Mobs in Kentucky’, 30 November 1878; ‘The Record of Murder’, 27 March 1879; and ‘Terrorism in Kentucky’, 29 October 1879.

‘Men, possibly the Hatfield family, display three of their dead’, c. 1880

During the second half of the nineteenth century, hundreds of eastern Kentuckians died during dozens of disparate political struggles throughout the region, which received national attention. The infamous Hatfield and McCoy feuds became synonymous with the region’s politics. As T.R.C. Hutton has shown, the idea of ‘feuding’ was largely a pejorative nomenclature that western and central Kentuckians used to oversimplify the complexity of Appalachian politics. This was especially the case after the assassination of William Goebel, during which approximately 500 Republican ‘mountain men’ barricaded the entrance to the state capitol to prevent State Democrats from appointing Goebel governor.

Source of Image: Kentucky Historical Society/ Hatfield and McCoy photographs/SC 1345

61st Inauguration, 10 December 2019

By the late nineteenth century, the frequency of assassinations and dueling was so common in Kentucky that resolutions were passed to ensure that the state’s governors had not participated in a duel. To this date, approximately half of the Oath of Office is designed to keep duelists out of office.

Violence in Western Kentucky: The Black Patch Tobacco wars and The Long Rivalry between Kentucky and Duke

Eastern Kentuckians did not have a corner on the practice of political violence in the state. As Suzanne Marshall has shown, western Kentucky was one of the world’s largest producers of black patch tobacco by the late nineteenth century. During the 1870s, tobacco production increased from 15,000,000 pounds to nearly 150,000,000 pounds. To challenge the expanding tobacco monopoly of James B. Duke’s American Tobacco Company, 70% of Kentucky farmers organized under the Planters’ Protective Association (PPA). By the end of 1910, more radical factions in the PPA—known as Possum Hunters, the Silent Brigade, or the Night Riders—used crop slashing, barn burning, overt physical violence and, at times, murder, to compel non-unionists to join rank. The Frankfort government responded by deploying Troopers, which preceded today’s Kentucky State Police. While the Tobacco Wars unfolded after the Goebel assassination, Goebel had effectively capitalized on emerging anti-trust sentiments throughout western Kentucky to secure the support of the Democratic Party.

In time, Kentuckians’ hostility toward the North Carolinian tobacco industry of James Duke manifested itself on the basketball court. Indeed, today’s rivalry between the University of Kentucky and Duke University developed long before Christian Laettner’s 1992 buzzer beater. The antagonism dates to the Southern Conference Tournament of 1930, during which Duke defeated Kentucky by 5 points in the semifinals. But before the Southern Conference Tournament, there was Black Patch, and its horrors and contestations were still in living memory when these two teams collided in Atlanta. The intensity of the teams’ contest was fired by the smoke of cured tobacco.

Source of Image: ‘In the Night Rider District of Kentucky, Troopers going on Duty’, front, c. 1910. Kentucky Historical Society/Ronald Morgan Kentucky Postcard Collection/Graphic 5/Graphic5_Box21_67

William Taylor, William Goebel and the Election of 1899

Governor William S. Taylor

Source of Image: Kentucky Historical Society/’The Battle for Governor in Kentucky: Photographs of the Conflict’ (1900)

Governor William Goebel

Source of Image: Kentucky Historical Society/Wolff, Gretter, Cusick and Hill Studios Negatives, Graphic 2/Graphic2_Box117_F7 (1900)

Poole Brothers, ‘Tourist Through Care Line, Louisville and nashville Railroad’, 1890

Source: David Rumsey Historical Map Collection, Stanford University

William Goebel was born in Pennsylvania into a German-speaking family on the eve of the American Civil War in 1856. At a young age, Goebel’s family relocated to Covington, Kentucky, where he launched an ambitious legal and political career during the following decades. He served as a State Senator throughout the late 1800s and built a state-wide campaign against the railway corporations in Kentucky, namely the Louisville and Nashville Railway. Goebel and his clients accused the L&N of excessive fees, low wages, and causing the depreciation of property values. As a Democrat in a state that was increasingly politically and ideologically aligned with the South, Goebel was an anti-corporation/anti-trust candidate. It was on this populist platform that he contested the gubernatorial election of 1899.

Goebel sought to break the Republicans’ grip on state power, which they had maintained since the Civil War. While Kentucky had remained neutral during the War, its political elites and ordinary citizens opposed secession. This resulted in the development of an influential Republican block that stood to benefit from industrialization during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries: a period often referred to as the Gilded Age, Progressive Era, or the Great Acceleration.

The 1899 Election was contested by the Republican, William S. Taylor, and William Goebel. After the ballots were counted, the Election Commission appointed Taylor governor. The Democrats, however, called foul play (citing polling irregularities). Goebel refused to concede. Soon thereafter, armed Democrats began patrolling the streets of Frankfort. Rumors circulated that the Democrat-controlled legislature aimed to swear Goebel into office, despite losing the election. The Secretary of State, Caleb Powers, a graduate of Centre’s College Law School, began organizing republicans in eastern Kentucky to travel to Frankfort immediately by rail. On 30 January 1900, with Taylor as Governor, William Goebel was shot from Powers’ office.

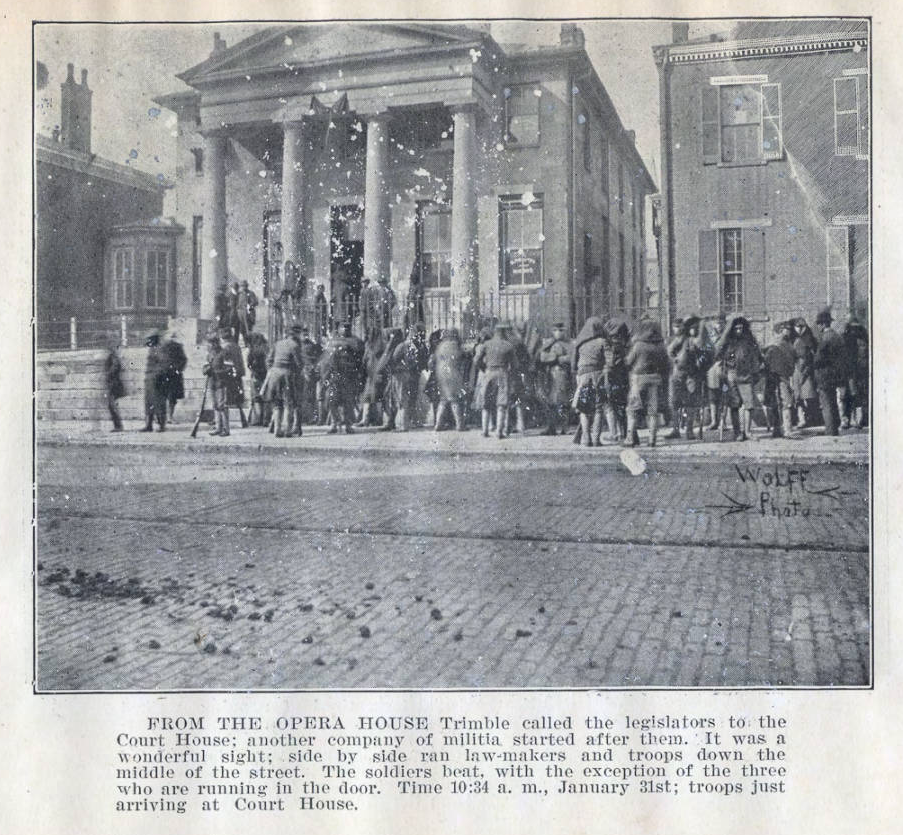

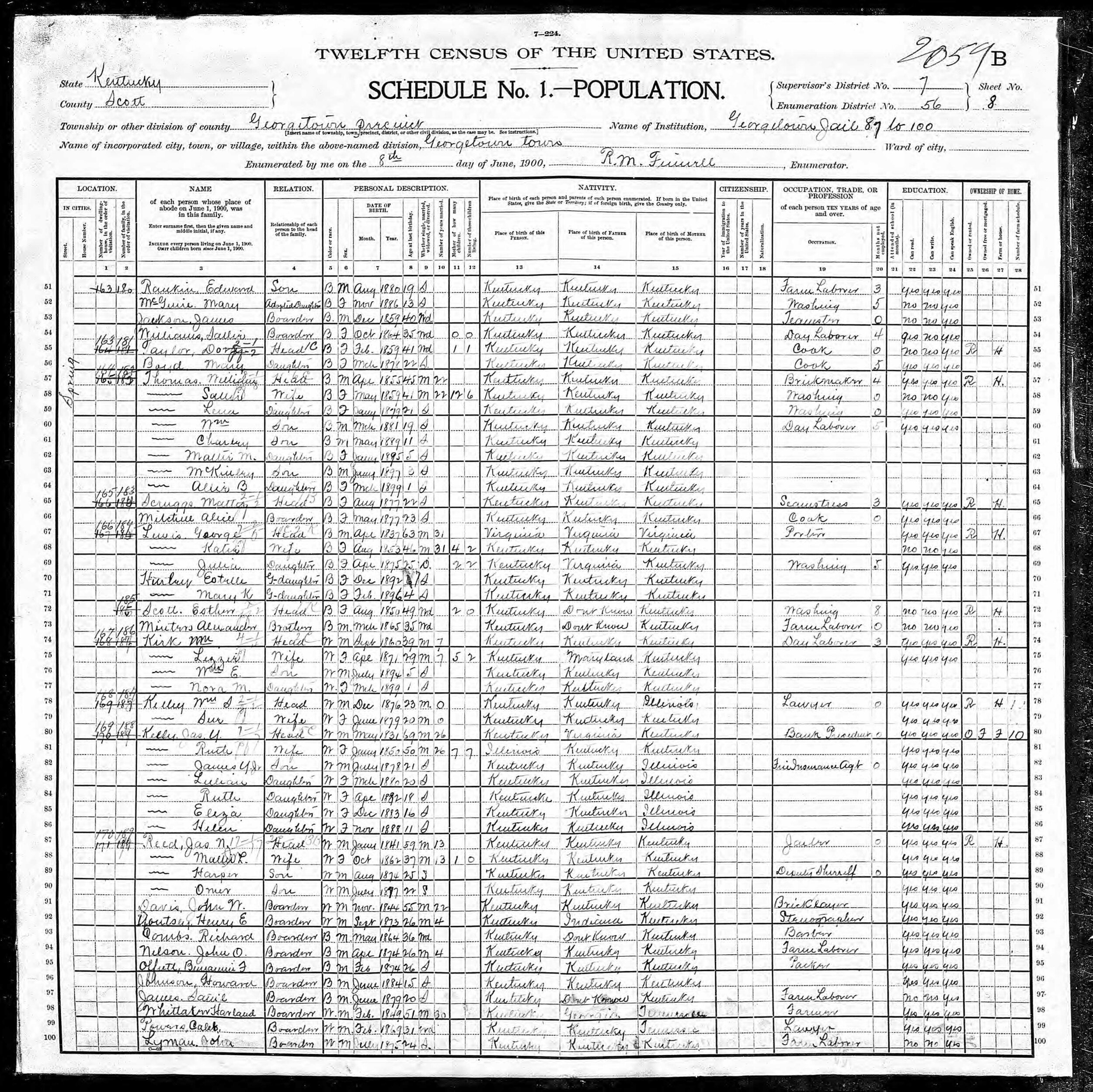

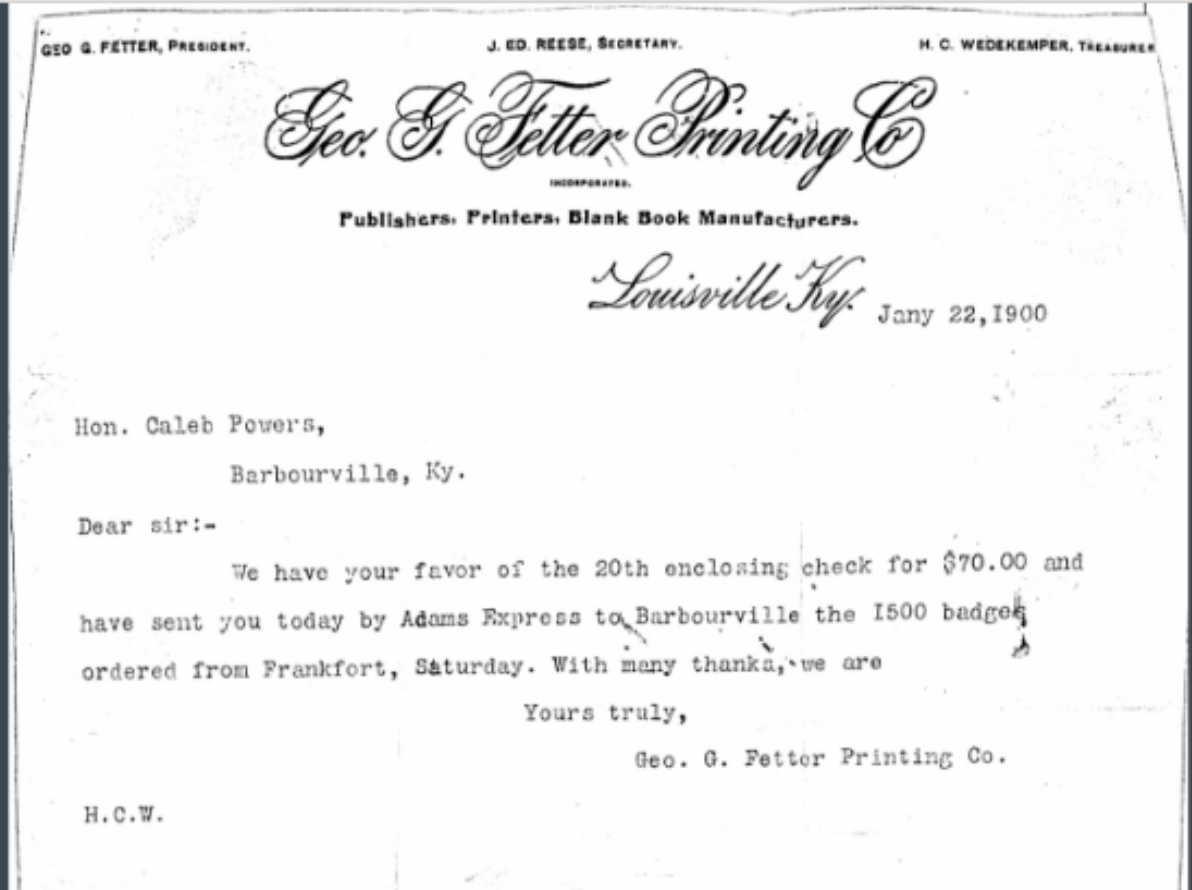

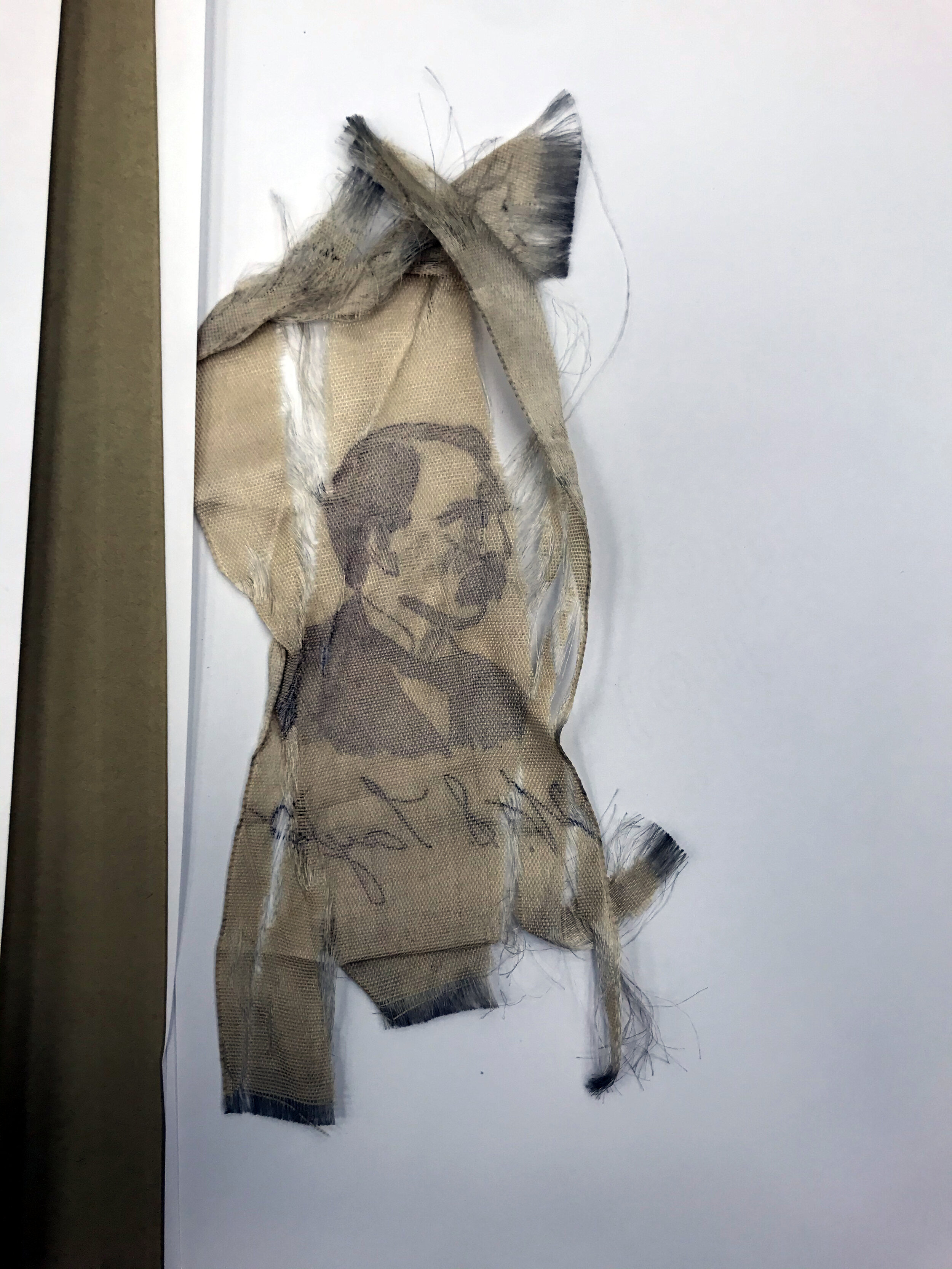

Remaining correspondence and material culture shows that Caleb and his brother, John, also a Centre graduate, sent around 1500 Taylor badges (campaign ribbons) one week prior to the assassination (image below). Following the organization efforts of the Powers, a group of no fewer than 500 ‘mountain men’ traveled by rail from London to Frankfort. Their mandate was to support the state militia and prevent any Democratic Congressman from entering into a government or pedestrian building, or meeting quorum, to appoint Goebel the next governor of Kentucky. Until Goebel died, no Democrat was to set foot in the capitol. Not to be outdone, the Democrats organized a clandestine meeting in an unguarded building, where they overturned the results of the election and appointed Goebel governor. The Oath of Office was administered at Goebel’s bedside. Goebel died four days after being shot.

The following images, provided by the Kentucky Historical Society, show how the military and an eastern Kentucky militia prevented Democrats from entering buildings throughout Frankfort. As T.R.C. Hutton has argued, the assassination and the surrounding deployment of armed militias nearly resulted in America’s first intrastate Civil War. At times, the militia was actively chasing Democrats, the latter of whom were literally racing to secure a safe space to appoint Goebel.

Source of Images: Kentucky Historical Society: (1) KY photographs, FF1.207; 2) Wolff, Gretter, Cusick and Hill Studios Negatives, Graphic2_Box117_F10; (3) ‘The Battle for Governor in Kentucky: Photographs of the Conflict’, Pamphlet, 2000SC15

Assassins and Centre College

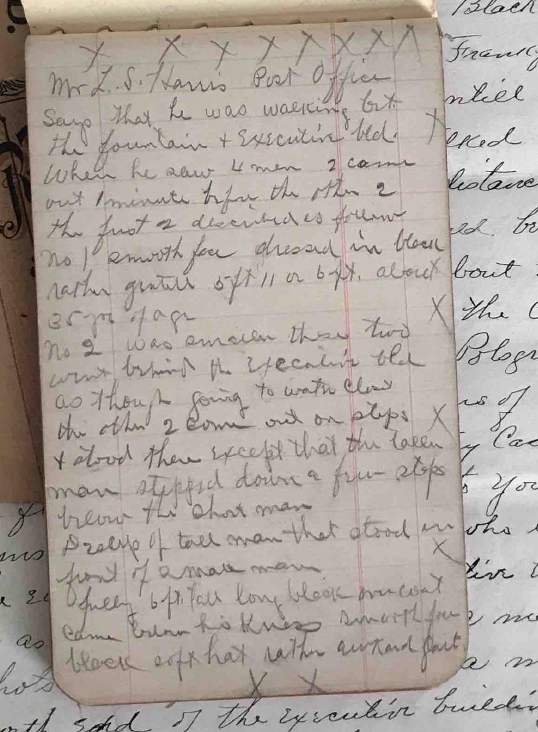

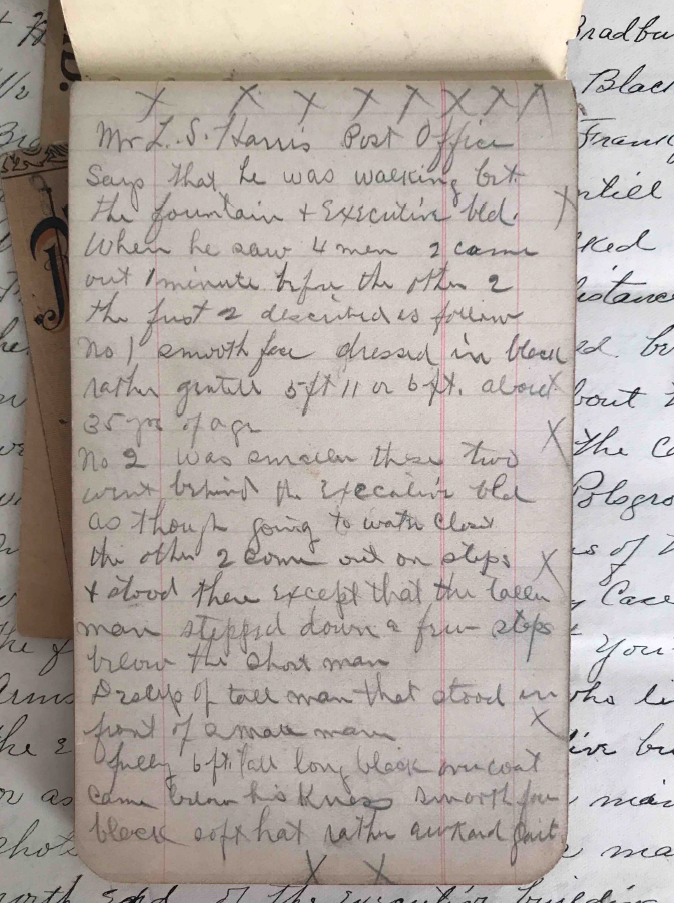

Following the assassination, the state launched an investigation that cost $100,000 (approximately $3,000,000 in today’s currency). The detectives’ reports are housed with the Filson Historical Society. Sixteen suspects were indicted for the murder; five of whom went to trial. Two were acquitted; and the subsequent trials—and state and national attention—soon centered on three men, each of whom went to multiple trials but were ultimately acquitted.

Caleb Powers, a graduate of Centre College, was accused of being the mastermind behind the assassination. He and his brother, John, also a Centre College graduate, worked to mobilize the militia (or mob) that stormed the capitol. It was also from Powers’ office that the assassin’s bullet was fired. Powers stood trial four times in seven years, resulting in two sentences to life in prison. Both sentences were overturned. During the third trial, Powers defended himself and addressed the jury for seven hours without interruption. Once he finally stopped, the exasperated jury voted that he should be hung. The verdict was overturned through the appellate courts. In total, Powers spent 8 years in prison, during which he wrote a memoir of the assassination: My own Story, an Account of the Conditions in Kentucky Leading to the Assassination of William Goebel.

Henry Youtsey was a 25-year-old court stenographer. During his trial, he confessed that he had sent a money order to Cincinnati for a box of steel-jacketed cartridges to pierce the steel vest that Goebel was believed to frequently wear. Youtsey also confessed that he had been in Caleb Powers’ office two days prior to the assassination, hanging out by the window with a gun across his lap. Youtsey spent eighteen years in prison, before being pardoned in 1919.

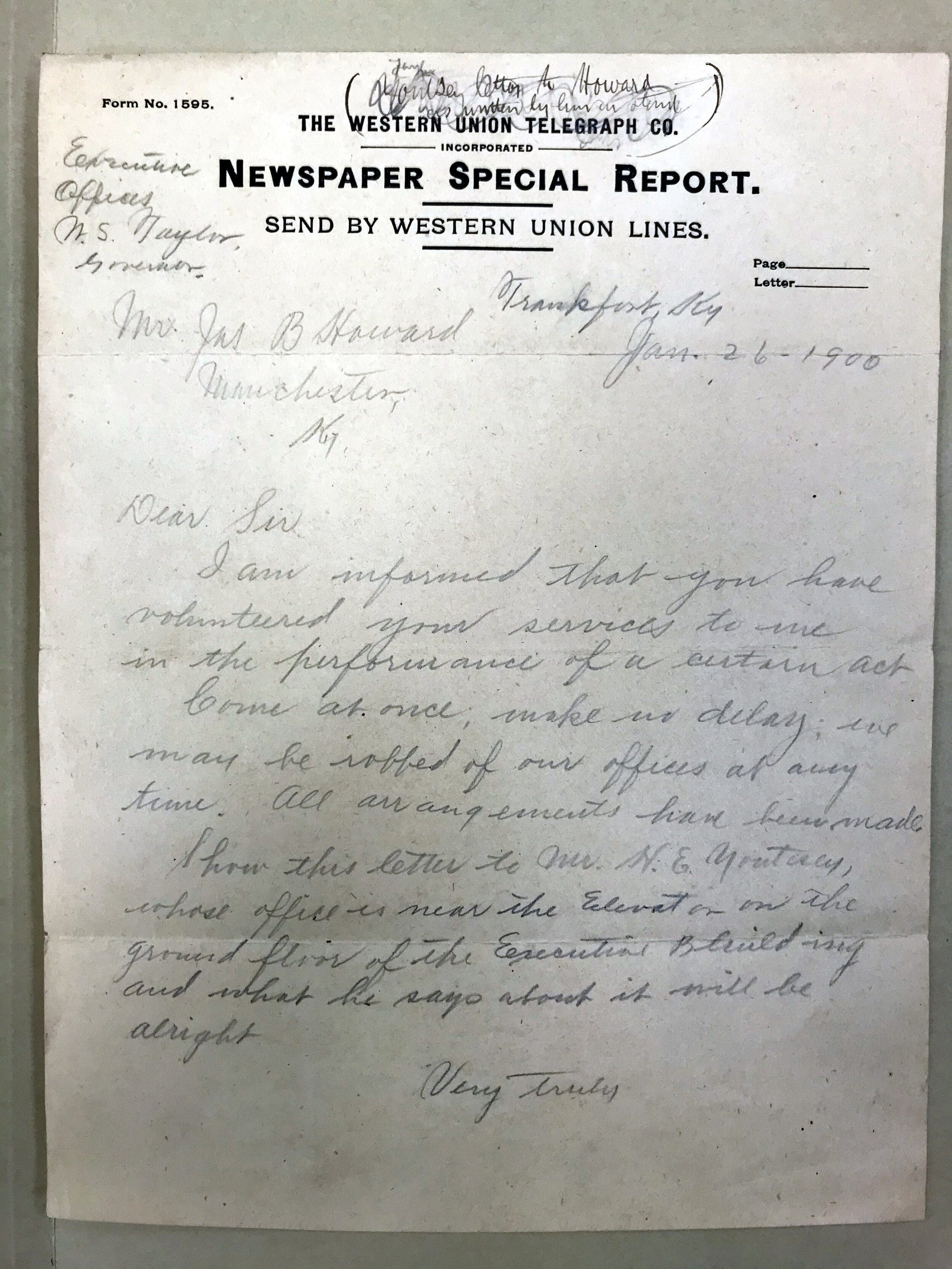

Jim Howard was accused of pulling the trigger. He stood trial on three occasions. The letter that Governor Taylor allegedly sent to Howard is maintained in the Scott County Court records. In the letter, Governor Taylor writes:

‘I am informed that you have volunteered your services to me in the performance of a certain act. Come at once, make no delay; we may be robbed of our offices at any time. All arrangements have been made.’

During the first trial, Howard was sentenced to hanging, which was quickly overturned by the appellate courts. During a second and third trial, he was sentenced to life in prison. He was ultimately pardoned in 1908.

Governor Taylor fled to Indiana after Goebel’s death. He never returned to Kentucky.

The first row of images shows Powers’ window, from whence the assassin’s bullet was fired (highlighted in yellow).

The second row of images includes: (1) Centre College’s list of law school graduates in 1898, including the two Powers (Kentucky Advocate, 8 June 1898). The second image is from the Twelfth Census of the United States, 8 June 1900, which documents Powers in jail (line 99). The next two pieces of evidence (a letter and badge) provide precise insight into Powers’ mobilization of an eastern Kentucky militia (Source: Kentucky Department for Libraries and Archives). The final letter is between Governor Taylor and the alleged assassin, Jim Howard (Source: Kentucky Department for Libraries and Archives).

the Making of a Martyr And the Distancing of Political Murder

Following Goebel’s murder, Kentucky Democrats busied themselves with the creation of postcards, woodcarvings, keepsake books, pamphlets and monuments. While William Goebel had long been a divisive personality in public life—among Democrats, as well—he was soon reimagined as a martyr, one who ‘devoted and gave his life in defense of the rights of the people’. In particular, a bulky statue of Goebel was cast and placed in front of Kentucky’s new capitol building in 1910. The statue’s engraving specifically stated that the governor had been ‘shot down by an assassin from the private office of the then Secretary of State’. The writing was on the wall. The Republican Caleb Powers—and by association, the entire Republican party—had blood on their hands.

The monument remained in place until December 1963, when the governor and legislature decided to distance Goebel from the memory of everyday politics. For some, the monument was simply a traffic hazard. Republicans wittingly suggested that the statue should be melted down into its original elements. During a gubernatorial election season, former Governor Happy Chandler and Governor Ned Breathitt criticized the movement of the statue in order to marshal support in northern Kentucky, whose communities questioned the relocation. More saliently, though, legislative debates unfolded shortly before and after the assassination of John F. Kennedy, who was murdered in late November 1963. Kentucky legislatures sought to illustrate that assassinations were a practice of the distant past by purging the memory and legacies of political murder from public life. While assassinations might occur elsewhere—Texas (JFK), New York (Malcolm X), Tennessee (MLK) and California (Robert Kennedy)—the omission of Goebel from the 1960s normalized Kentucky politics during a period of frequent national political murder.

The images below show an example of a postcard (Kentucky Historical Society) and scrapbook of the period (Margaret I. King Library, Special Collections of the University of Kentucky). Goebel’s statue in front of the New and Old Capitol are also presented (Source of Image: Kentucky Historical Society).

Music and Popular Memory

By the early twentieth century, artists and musicians reflected upon the assassination of Goebel. Following a much older tradition of murder ballads, eastern Kentuckians reinforced early hagiographies of the life and death of the Governor, which tended to underscore Goebel’s sacred work, populism, and martyrdom. These songs also captured the disdain and distrust with which ordinary Kentuckians viewed the affairs of state. Also, it is unclear to what extent eastern Kentuckians used songs and oral histories to distance themselves from the controversial role on the region’s mob in the assassination scheme.

The Death of William Goebel, As read by Addie Graham (1900–1978)

Our grand ole state is left in shame since the death of William Goebel

I hope you will not scorn his name, his works were great and noble

He labored hard through this campaign, with cautious steps he travelled

We think he touched the secret spring, great mysteries he unravelled

This famous man with wit and skill, seriously he was thinking

He bade his friends to all keep cool, in death he fast was sinking

Now his silver voice is hushed in death, as the shades of evening gather

He owes submission (?) to the laws of God, and our spirit ascends to the Father

His breath came short and very quick, loved ones around him hover

They wait the fast approaching train, that bore his absent brother

Alas, his coming was too late, his life he had departed

Three sad ones left by his bedside, bereaved and broken hearted

Kentucky greatly feels his lost, for he was one of the bravest

He died a martyr at his post, his murder was outrageous

Poor Goebel he was cruelly shot, while going on his mission

Two brothers left and sisters (too or two), to mourn their sad condition

We think it was a burning shame, for it was done for wages

It will not be erased by time, from off their history’s pages

Rise up ye honest hearted men, the present is exciting

Honesty is sure to win, the laws will do our fighting

Oh, Taylor strong and daring guard, with loaded guns are waiting

To cover up this bloody crime, his friend they are debating

Our final courts will be on high, to try such cruel cases

Our judge and jury will be there, with true and honest faces

Sources

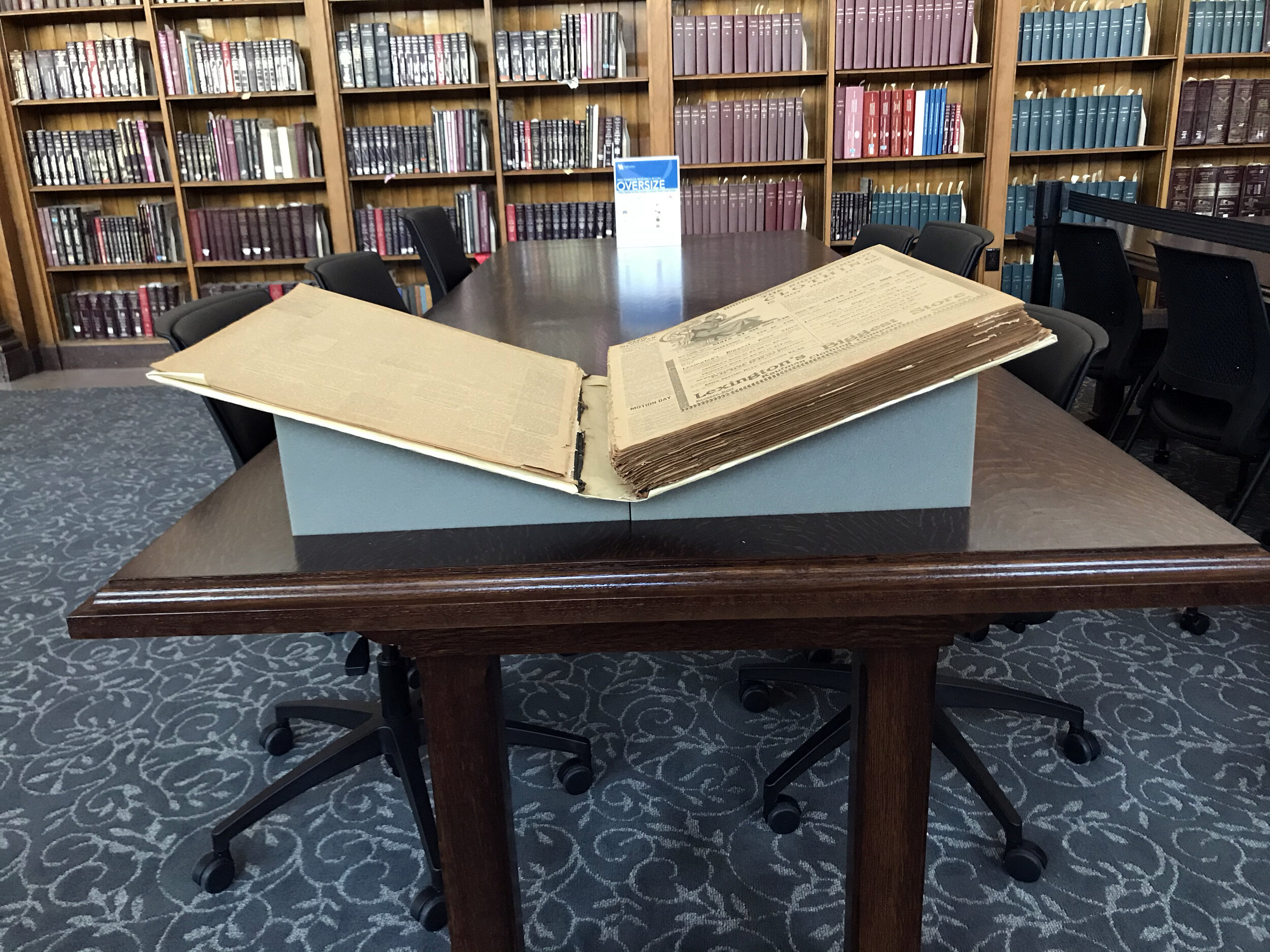

In these images, the different types of sources that students consulted are seen. These include the clothes that Goebel wore at the time of his assassination, detective reports, trial transcripts, newspapers, and popular magazines.

For comments, questions, or suggestions, please reach out: HERE